Heidegger 101

Into the Heideverse: Substituting experience for thought

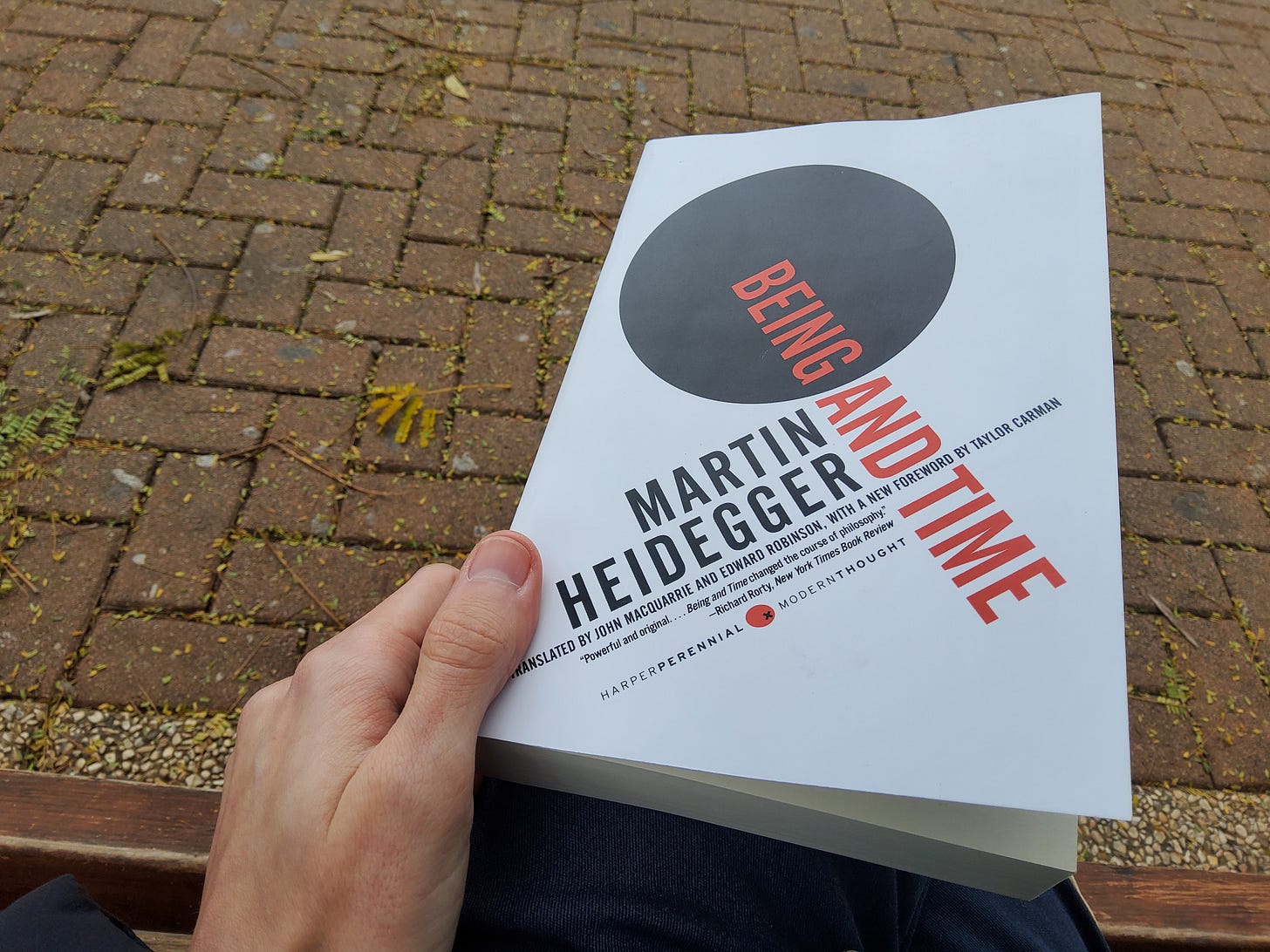

1From some late-middle-teens onward I had Heidegger in the back of my mind as someone I should get to know better, but didn't really have a clue from where to start - so I asked a friend. He recommended I take a look at History of the Concept of Time - based on Heidegger's lectures at the University of Marburg in the summer of 1925, and a precursor to his magnum opus, Being and Time, published in 1927. So I took a look.

Now, a year+ later, let me report back: If you have absolutely no background in Heidegger, do not start from the extremely opaque lectures, given to graduate students who were already well-versed in his thinking and current-day continental philosophical trends2.

Here's my alternative:

The Guide

Start with a brief glimpse into the backstory of Phenomenology - the core of Heidegger's thinking:

Next: A brief intro of Heidegger's life and stages of thought.

Then, this excellent threadapalooza from Zohar Atkins3, really gives a sense of the range and breadth of his work and personality (flirting - ? - with the antisemitic, fascist zeitgeist of his time).

If you still feel an itch for some of the real stuff, I'd first take a look at the Stanford or Internet Encyclopedias - both excellently written with the care of a literal reader in mind: lucid, well-presented, and thoroughly researched. (I'd also get a sense of hermeneutics while I'm at it: here). Encyclopedias shouldn’t seem scary or give you the shivers.

I also found that going back and forth between the encyclopedia entries, the podcast, the book itself, and some other secondary lit (such as George Steiner’s Martin Heidegger) - to be immensely useful. Each uses its own language, articulation, and examples - until things fall into place. Tyler is correct - reading in clusters actually works (tbh, I’m taking him a bit out of context).

And for the final push, golden - a podcast that runs through Being and time - slow but unrelenting:

From the description:

Apply-Degger: Heidegger's Project in Being and Time with Simon Critchley

Apply-degger is a long-form, deep dive into the most important philosophical book of the last 100 years. Each episode of this podcast series will present one of the key concepts in Heidegger’s philosophy. Taken together, the episodes will lay out the entirety of Heidegger project for people who are curious, serious and interested, but who simply don’t have the time to sit down and read the 437 densely-written pages of the book. It is our hope that this series will show how Heidegger’s thinking might be applied to one’s life in ways which are illuminating, elevating and beneficial. We are asking the listener to slow down, take their time, open their ears and think deeply. What is said in these episodes will hopefully be clear and helpful, but not easy. We are not interested in easy. Let’s try something else for once.

“Apply-degger is not intended for everyone. I am not seeking to make philosophy simple or offer patronizing banalities about life. These are not Ted talks. In many ways, they are the opposite. They are slow, clear and intimate explorations of Heidegger’s ideas in Being and Time. It is my conviction that genuine philosophy can be explained simply and clearly. But it takes the time that it takes. And that can’t be rushed.” – Simon CritchleyEvery. Word.

They deliver4.

My journey towards the clearing

I tried my hand at Heidegger’s work twice. The first was a number of years ago and abandoned after doing 1-3 but with no progress - the ideas just didn't make any sense. More recently, I returned and realized I’d made a critical mistake: I was trying to understand what should have been experienced5. Up to that point, most of the information I consumed was mostly analytical in nature - math, history, graphs, data - which required understanding rather than to be felt or experienced6, or at least, it works through those modes as well. With Heidegger, I came to learn, this was impossible. To understand directly, a reroute was needed: reading first, followed by a deliberate push away from understanding and towards experience, then returning to the text and rereading, now allowing understanding to be present as usual. The reroute is needed because phenomenology isn’t something the mind grasps, but rather a piece of reality to be experienced by ‘being’ itself. Until then, keep praying :/

One more tip: let it marinate. Read a bit, let it rest. Go out into the world. Engage. Come back. Reread.

Practically, if I’m allowed to use the word in this context, one of the most important things I got from the ‘Heidiverse’ is a new lens of appreciation, some sort of upgrade in felt-sense, towards that ‘which is’. Walking down a TLV street one fine morning and just realizing the fact that ‘I am’ and that ‘is’ness is there - that’s all I need7. some sort of better feel to the pulse of reality. Lucky to have it8.

Another resource I didn’t use much but seems cool. Hubert Dreyfus is a classic as well - though reservations. And chatgpt…

Poetry was another backhand gateway into some of H’s ways of being, they immerse you in the experience - if you allow yourself to be absorbed. They explicitly spoon-feed that which can’t be said, as Heidegger put it:

“The thinker says what being is; the poet names what is holy”

Hope to return to HCT, B&T, What is Called Thinking?, What is Metaphysics?, Heidegger's definition of truth as unconcealement, his relationship to Zen, and more. Sooner than later. One day.

Some pics:

I never finished it myself - Ep. 13 and onward make little sense to my current self, unsure if I’m reading the concept of time correctly or not. Hope to revisit.

He introduced me to some of the best poems I’ve ever read - e.g. The Idea of Order at Key West - through which he elucidates Heideggerian concepts.

Here is George Steiner:

If we grasped him readily or were able to communicate his intent in other words than his own, we would already have made the leap out of Western metaphysics. We would, in a very strong sense, no longer have any need of Heidegger. It is not "understanding" that Heidegger's discourse solicits primarily It is an "experiencing," an acceptance of felt strangeness. We are asked to suspend in ourselves the conventions of common logic and unexamined grammar in order to "hear," to "stand in the light of" - all these are radical Heideggerian notions - the hearing of elemental truths and possibilities. of apprehension long buried under the frozen crust of habitual, analytically credible saying.

Another exemplary passage:

The next example is among Heidegger's touchstones:

A painting by van Gogh. A pair of rough peasant shoes, nothing else. Actually the painting represents nothing. But as to what is in that picture, you are immediately alone with it as though you yourself were making your way wearily homeward with your hoe on an evening in late fall after the last potato fires have died down. What is here? The canvas? The brushstrokes? The spots of color?

All of these things, which we so confidently name, are there. But the existential presentness of the painting, that in its existence which reaches into our being, cannot be adequately defined as the material assemblage of linseed oil, pigment, and stretched canvas. We feel, we know, urges Heidegger, that there is something else there, something utterly decisive. But when we seek to articulate it, "it is always as though we were reaching into the void."

We are at the heart of the argument. Let me attempt a further illustration though, damagingly I think, Heidegger continually passes it by.

To the majority of human beings, music brings moments of experience as complete, as penetrating as any they can register. In such moments, immediacy, recollection, anticipation are often inextricably fused. Music 'enters' body and mind at manifold and simultaneous levels to which classifications such as “nervous,” “cerebral,” “somatic” apply in a rough and ready way. Music can sound in dreams. It can recede from accurate recall but leave behind an intricate ghostliness, a tension and ‘felt lineament of motion’ that resemble, more or less precisely, the departed chord or harmony or relations of pitch. No less forcefully than narcotics, music can affect our mental and physical status, the minutely meshed strands of mood and bodily stance that, at any giver point, define identity. Music can brace or make drowsy; it can incite or calm. It can move to tears or, mysteriously spark laughter or, more mysteriously still, cause us to smile in what would seem to be a singular lightness, a mercurial mirth of mind as centrally rooted in us as is thought itself. We have known since Pythagoras that music can heal and since Plato that there are in music agencies that can literally madden. Melody, writes Lévi-Strauss, is the mystère suprème of man's humanity. But what is it? Is melody the being of music, or pitch, or timbre, or the dynamic relations between tone and interval? Can we say that the being of music consists of the vibrations transmitted from the quivering string or reed to the tympanum of the ear? Is its existence to be found in the notes on the page, even if these are never sounded (what conceivable ontological status have Keats's "unheard melodies")? Modern acoustical science and electronic synthesizers are capable of breaking down analytically and then reproducing any tone or tone-combination with total precision. Does such analysis and reproduction equate with, let alone exhaust, the being of music? Where, in the phenomenon "music," do we locate the energies which can transmute the fabric of human consciousness in listener and performer?

The answer eludes us. Ordinarily, we search for metaphoric description. Wherever possible we consign the question either to technicality or to the limbo of obviousness. Yet we know what music is. We know it in the mind's echoing maze and in the marrow of our bones. We are aware of its history. We assign to it an immensity of meaning. This is absolutely key. Music means, even where, most especially where, there is no way whatever to paraphrase this meaning, to restate it in any alternative way, to set it down lexically or formally. "What, then, is music?" asks the fictive questioner from another planet.

We would sing a tune or strum a piece and say, unhesitatingly, ""This is music." If he asked next, "What does it mean?" the answer would be there, overwhelmingly, in us, but exceedingly difficult to articulate externally. Asked just this question of one of his compositions, Schumann played it again. In music, being and meaning are inextricable. They deny paraphrase. But they are, and our experience of this "essentiality" is as certain as any in human awareness.

Halting as it is, this analogy may suggest a first approximation to Heidegger's concept of being. Here too there is brazen obviousness and impalpability, an enveloping nearness and infinite regress. Being, in the Heideggerian sense, has, like music, a history and a meaning, a dependence on man and dimensions transcending humanity. In music, intervals are charged with sense. This, as we shall see, may help us to understand Heidegger's relation to being of an active ‘nothingness’ (das nichtende Nichts, Sartre's le néant). We take the being of music for granted as we do that of the being of being. We forget to be astonished.

Similarly to how psychoanalytic writing cannot be understood purely through reading alone, in the Ether. Only by being applied out in the wild does it even start to make sense.

It’s easier to say מודים with that felt-experience present.

Parenthetically, I found interesting these studies which show how golf ‘swing thoughts’ are counterproductive - the more you think deeply about the swing and how to perfect it, the worst it turn out. This aligns perfectly with the Heideggerian (golf club ;) Ready-to-hand vs Present-at-hand distinction, where the former is ‘closer’ and better grips the phenomena, while the latter is reflective and therefore disrupts our connection to the present reality.

Very cool. Appreciate the effort. Looks like a labour of love to me. Or the experience of…

I second the Apply-Degger podcast.